(Note: Over the last few days I've been going through a lot of 1920s Pittsburgh newspapers and admiring their coverage of Pittsburgh's semi-pro baseball. Because the coverage was so good, and the quality of play was also high, I'm going to spend some time writing about Pittsburgh semi-pro baseball. Hope you think it's as interesting as I do.)

1924 was a year of woe. Heavy rain made it impossible to play baseball the entire first month of the season. As most of the teams were paying their players by the week, this was a great blow to their finances. To make matters worse, an industrial depression hit the region, and the steel mills laid off men. Even when the season was underway the games were characterized by poor attendance and even worse gate receipts: few of the ball parks were enclosed, and it was easy for fans to watch the play without paying.

At one game, only $185.65 could be collected from a crowd of 4,000 fans, while it had cost the teams $255 to put on the game. It was estimated that less than a third of the fans had paid a cent. The players and umpires had to get their pay no matter what, and the teams did very badly financially. Few if any made a profit, and often the managers had to dig into their own pockets to keep the teams alive.

The umpires proved to be another thorn in the side of managers; they were complained of unanimously. The Pittsburgh Umpires' Association, it was said, was foisting off many unqualified umpires for games, and their decisions were little better than guesswork. This was particularly scandalous in light of their pay, which at $5 to $10 a game represented a real expense to the teams.

|

| A few of the reviled. Pittsburgh Post, 1923-5-20, p.32 |

Yet another complaint was the small number and poor quality of the ball parks. Fred P. Alger, who was the primary sandlot writer of the Post, began his article on the parks by saying: "Pittsburgh can proudly boast of having the worst sandlot ball diamonds in the country." The fields were tiny, and "in many cases a base hit rule must be put into effect during big games to cover the shortage of playing space." The city of Pittsburgh had no thought for the bare necessities of baseball. It was a case of sheer negligence. "The cry has been heard that there are not any available plots suitable for ball grounds left but a ride over the city streets reveals plenty of vacant land where ball parks might be placed if some of the city fathers would emerge from their lethargy long enough to say something in favor of such an action."

But despite the rain, despite the failures of mines and mills, despite "pikers" who watched games free, despite the shoddy umpiring and scanty parks, good baseball was played.

Though the Twilight Leagues made no money, they did produce some fine pennant races.

The leagues' pennant winners:

Ardmore League: Ardmore All-Stars

Blair County League: Claysburg

Crafton-Ingram League: Presbyterians

Knights of Malta League: Gold Cross Commanders

Lawrence County: Italian A.A. of New Castle

Northside Twilight League: Millvale

South Hills League: Broadway

Triple Link League: Gastonville

Valley League: Rankin Facades

Venango County: Reno

Westinghouse League: Section I.K. & Z.

Ardmore League: Ardmore All-Stars

Blair County League: Claysburg

Crafton-Ingram League: Presbyterians

Knights of Malta League: Gold Cross Commanders

Lawrence County: Italian A.A. of New Castle

Northside Twilight League: Millvale

South Hills League: Broadway

Triple Link League: Gastonville

Valley League: Rankin Facades

Venango County: Reno

Westinghouse League: Section I.K. & Z.

The Northside Twilight League was shaken up before the season even began when it had to replace four of its six teams. The Northside Board of Trade, Lutz & Schramm, and the J.J. MacPhees all expired, while the Homewood Tressers left the league to play independent ball.

|

| Pittsburgh Post, 1923-8-19, p.29 |

Of these, the Northside Board of Trade was the most mourned. Under the leadership of Jimmy Black the team had won the Northside Twilight League every one of the five seasons of the league's history, but Black resigned after the 1923 season because he felt he was not appreciated, and no one took his place. (1924-4-08) Art Rooney was asked to replace him, but refused, and instead played outfield for Jeannette.

Yes, that Art Rooney. Before Art Rooney founded the Pittsburgh Steelers he was a minor league and semi-pro outfielder. He was the top sandlot Pittsburgh home run hitter in 1923, at one point hitting five home runs in seven games.

The departing teams were replaced by Millvale, the Etna Elks, Brushton, and Immaculate Heart. The league's only holdovers for 1924 were the Fineview Board of Trade Highlanders and the Pleasant Valley Smilers.

While in Pittsburgh the league teams probably outnumbered the independents, it was an independent team that won for itself the claim of champion of Pittsburgh in 1924.

Pittsburgh's elimination series to determine their class AAA representative for the National Baseball Federation championship series began in early August, and 27 teams took part. Many of the teams dragged their heels over playing their games, and fan interest dragged too, but the series finally narrowed down to two teams: Millvale, of the Northside Twilight League, and the Harmarville Consumers, who in 1923 had been Pittsburgh's champions but had lost in the National Baseball Federation finals.

Cliff Barton, the Consumers' manager, did a heroic job in taking the Harmarville Consumers to meet Millvale in the Pittsburgh finals in 1924; it was heroic of him just to keep the team from folding mid-season. Things had looked dire for the team when Harmarville's mine closed mid-season, as most of the players had jobs in the mine. A few of the players left the team but he signed new players to take their places, convinced the rest of the players to stay, and kept the team running.

As of September 7 Millvale had a record of 36-13-4, but their record was inflated by a 22-2 mark in the Northside League, losing their only two games to the Etna Elks. Against independent teams their record was a more pedestrian 14-11-2.

As of August 3, the Consumers had a record of 28-21-4. The Consumers ended up beating Millvale 3-0, September 10, to repeat as champions of Pittsburgh. They advanced far in the National Baseball Federation series, making it to the national finals. Under Barton the Consumers were universally liked for their fairness, and "every [Pittsburgh] sandlot fan and baseball player [were] pulling for Barton's mining outfit" in the NBF finals. But it was to no avail. The Consumers again lost in the NBF finals, this time to the Grennan Cakes of Cleveland.

On September 14 the Pittsburgh Post published a list of the top pitchers:

W L T PCT

10 1 0 .909 Walter Cannady, Homestead Grays

17 2 3 .895 Sam Litvaney, Etna Elks

24 3 2 .889 Carl Poke, Bellevue

12 2 0 .857 Alex Pearson, Harveys

16 3 0 .842 Bill Helmick, Uniontown.

30 6 1 .833 Abe Martin, Harmarville Consumers

18 5 7 .783 Joe Drugmond, Beaver Falls Elks

7 2 2 .778 Verne Hughes, Ambridge

13 4 0 .765 Joe Semler, Beaver Falls Elks

28 9 0 .757 Oscar Owens, Homestead Grays - threw six shutouts

27 10 2 .729 Lefty Williams, Homestead Grays

18 7 0 .720 Billy Edwards, Harmarville Consumers - threw no-hitter on July 4

30 12 0 .714 Zip Wenzel, Harmarville Consumers

15 6 0 .714 Johnny Pearson, Braddock Elks

18 8 0 .692 Jimmy Uchrinsko, Beaver Falls Elks

11 5 1 .688 Clyde Gatchell, Scottdale

11 5 4 .688 Ed Rile, Homestead Grays

11 5 1 .688 Al Studt, Homewood Tressers

13 6 4 .684 Carl Stewart, Homewood Tressers

14 7 4 .667 Joe Miller, Harmarville Consumers

28 15 2 .651 Leo Carroll, Millvale

18 10 1 .643 Harry Beatty, Charleroi

10 6 0 .625 Joe Page, Harmarville Consumers

10 8 1 .556 Bimmy Steele, Jeannette

13 12 1 .520 Art Shaw, Ambridge

If you add up the win-loss records of the pitchers listed with Harmarville and the Homestead Grays, you would get records of 112-38-5 for Harmarville and 76-25-6 for the Grays. However, that's not even close to being accurate for Harmarville; many or even most of Pittsburgh sandlot pitchers played for multiple teams, so in many cases only a fraction of their listed record came with their listed team.

That didn't apply to the pitchers for Cum Posey's Homestead Grays, who could only pitch for the Grays. The Grays actually played close to 150 games in 1924, according to the Pittsburgh Gazette 1924-9-21, p.25.

Of the Homestead Grays on the list, only Lefty Williams was primarily a pitcher throughout his career. He had a 12-6 record and 4.78 ERA in the Negro Leagues. Walter Cannady, the leading sandlot pitcher by percentage, played infield in the Negro Leagues. He hit .320 in the Negro Leagues between 1922 and 1945. Oscar Owens, top winner of the Grays, mostly played outfield in his two seasons in the Negro Leagues, in which he hit .398 in 61 games with a 3-5 record on the mound. Ed Rile was a pitcher from 1920 to 1927, and a first baseman from then on. For his Negro League career he had a .316 average, 37 home runs, 51-36 record, and 3.33 ERA. He led the Negro National League in ERA in 1923 with a mark for 2.53 for the Chicago American Giants, and in OBP in 1928 with a sweet .425 for the Detroit Stars.

W L T PCT

10 1 0 .909 Walter Cannady, Homestead Grays

17 2 3 .895 Sam Litvaney, Etna Elks

24 3 2 .889 Carl Poke, Bellevue

12 2 0 .857 Alex Pearson, Harveys

16 3 0 .842 Bill Helmick, Uniontown.

30 6 1 .833 Abe Martin, Harmarville Consumers

18 5 7 .783 Joe Drugmond, Beaver Falls Elks

7 2 2 .778 Verne Hughes, Ambridge

13 4 0 .765 Joe Semler, Beaver Falls Elks

28 9 0 .757 Oscar Owens, Homestead Grays - threw six shutouts

27 10 2 .729 Lefty Williams, Homestead Grays

18 7 0 .720 Billy Edwards, Harmarville Consumers - threw no-hitter on July 4

30 12 0 .714 Zip Wenzel, Harmarville Consumers

15 6 0 .714 Johnny Pearson, Braddock Elks

18 8 0 .692 Jimmy Uchrinsko, Beaver Falls Elks

11 5 1 .688 Clyde Gatchell, Scottdale

11 5 4 .688 Ed Rile, Homestead Grays

11 5 1 .688 Al Studt, Homewood Tressers

13 6 4 .684 Carl Stewart, Homewood Tressers

14 7 4 .667 Joe Miller, Harmarville Consumers

28 15 2 .651 Leo Carroll, Millvale

18 10 1 .643 Harry Beatty, Charleroi

10 6 0 .625 Joe Page, Harmarville Consumers

10 8 1 .556 Bimmy Steele, Jeannette

13 12 1 .520 Art Shaw, Ambridge

If you add up the win-loss records of the pitchers listed with Harmarville and the Homestead Grays, you would get records of 112-38-5 for Harmarville and 76-25-6 for the Grays. However, that's not even close to being accurate for Harmarville; many or even most of Pittsburgh sandlot pitchers played for multiple teams, so in many cases only a fraction of their listed record came with their listed team.

That didn't apply to the pitchers for Cum Posey's Homestead Grays, who could only pitch for the Grays. The Grays actually played close to 150 games in 1924, according to the Pittsburgh Gazette 1924-9-21, p.25.

Of the Homestead Grays on the list, only Lefty Williams was primarily a pitcher throughout his career. He had a 12-6 record and 4.78 ERA in the Negro Leagues. Walter Cannady, the leading sandlot pitcher by percentage, played infield in the Negro Leagues. He hit .320 in the Negro Leagues between 1922 and 1945. Oscar Owens, top winner of the Grays, mostly played outfield in his two seasons in the Negro Leagues, in which he hit .398 in 61 games with a 3-5 record on the mound. Ed Rile was a pitcher from 1920 to 1927, and a first baseman from then on. For his Negro League career he had a .316 average, 37 home runs, 51-36 record, and 3.33 ERA. He led the Negro National League in ERA in 1923 with a mark for 2.53 for the Chicago American Giants, and in OBP in 1928 with a sweet .425 for the Detroit Stars.

The Post considered Carl Poke to be the real top right hander, as "Cannady was not assigned to any regular turn with the Grays while Litvaney made his mark in the Northside and Monongahela Division League wherein some mediocre teams held forth." Abe Martin was the top lefty.

Though you wouldn't have been able to tell by looking at his 12-2 record, Alex Pearson was 46 in 1923. Reportedly, his pitching career began in 1894 and lasted until 1936. He had a 2-6 record with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1902, a 1-2 record for the Cleveland Indians in 1903, and pitched in the Eastern League and New England League from 1908 to 1916, winning 62 games against 24 losses for the Lawrence Barristers from 1911 to 1914.

Joe Drugmond started out badly with Jeannette and had lost five games before he left for the Beaver Falls Elks and began winning. Leo Carroll, despite his 28-15 record, was listed with Bimmy Steele, Art Shaw, Clyde Gatchell and Harry Beatty among prominent pitchers who had not lived up to their expectations in 1924.

|

| Pittsburgh Post, 1924-8-3, p.28 |

Though you wouldn't have been able to tell by looking at his 12-2 record, Alex Pearson was 46 in 1923. Reportedly, his pitching career began in 1894 and lasted until 1936. He had a 2-6 record with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1902, a 1-2 record for the Cleveland Indians in 1903, and pitched in the Eastern League and New England League from 1908 to 1916, winning 62 games against 24 losses for the Lawrence Barristers from 1911 to 1914.

Joe Drugmond started out badly with Jeannette and had lost five games before he left for the Beaver Falls Elks and began winning. Leo Carroll, despite his 28-15 record, was listed with Bimmy Steele, Art Shaw, Clyde Gatchell and Harry Beatty among prominent pitchers who had not lived up to their expectations in 1924.

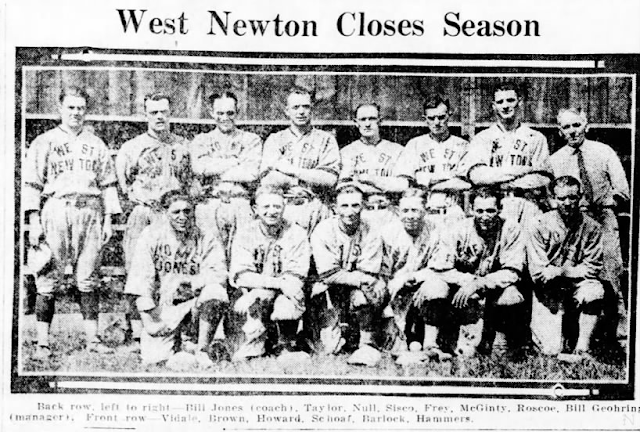

Danny Taylor of West Newton was the top batter of 1924. In 41 games he hit .507 with 22 home runs, 11 doubles, 38 singles, and 32 walks. He would go on to play in the major leagues for nine seasons, hitting .297 with some power. According to the Uniontown Morning Herald in 1926, as quoted in his SABR bio, he also hit 19 home runs for West Newton in 1925, including two in one inning. West Newton had a record of 27-13-1 in 1924.

|

| Pittsburgh Post, 1924-9-7, p.26 |

1924 was also marked by the rising number of college players on the sandlots. Impressed by the success of college men in the majors and the growing quality of play at the colleges, the sandlot teams were eager to sign college stars. Bellevue, one of the best teams, had two University of Pittsburgh men on their pitching staff in the Steve Swetonic and Alf Schmidt. Duquesne University had about a dozen of its players with Pittsburgh teams, and the University of Pittsburgh had at least half a dozen of their other players in addition to Swetonic and Schmidt starring in semi-pro. Other colleges represented on the sandlots included Penn State, Bucknell, Bellefonte, Saint Francis, and Waynesburg. (1924-7-06)

George "Ziggy" Walsh, star catcher for the Braddock Elks, set a mark for toughness. On July 27th it was noted he had not missed a game behind the plate all season - very impressive for a catcher. But his mettle was truly tested on September 2nd. The Elks were playing against Millvale in an elimination series game they desperately needed to win. Walsh had a broken finger, but as the Elks had no other catcher he unwound his bandage, set aside his splints, and caught the game. The Elks were three-hit by Leo Carroll and lost 4-2, but it was still a game of glory for Walsh. (Note box)

|

| Pittsburgh Post, 1925-5-31, p.33 |

The Harmarville Consumers had a strange pair in their second baseman Frank Anthony and their catcher Bill Schulties. Schulties was well over six feet tall, the tallest player in the district, while Anthony was not even five feet tall.

|

| Pittsburgh Post, 1924-9-7, p.26 |

The article of September 7th reported that "Anthony is considered by many as the best lead-off man in local ranks, having a hard stance at the plate which makes pitching to him a hard proposition, and along with it Frank is an eagle eye at looking the ball over and hits hard and timely. Schulties is the team's steady catcher and this year has been going great, having worked a majority of the games back of the bat for Cliff Barton's team."

They stuck together the next year, both signing to play with Homewood. (1925-3-22)

They stuck together the next year, both signing to play with Homewood. (1925-3-22)

Another feature of the Pittsburgh sandlots were the old major leaguers, past their prime but still playing for the fun of it. They didn't play for any of the top teams, but the fact that they were still out on the diamond at all is impressive.

|

| Pittsburgh Post, 1924-7-27, p.24 |

At 49, the all-time great Honus Wagner was the regular first baseman for the Carnegie Elks. Former Pirate pitching star Deacon Phillippe kept busy at 52 by umpiring, scouting for the Pirates, and pitching a game from time to time. Dutch Jordan, 44, who had played for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1902 and 1903, was now a policeman, and played second base for Brentwood. Frank Killen who had won 36 games for the Pirates in 1893, but by 1924 was 53, was reported in the article to have thrown two scoreless innings just the previous week. (I was not able to find any other reports of him playing in 1924.)